For those concerned about the long-term impact of open burning/open detonation of conventional munitions at Blue Grass Army Depot (BGAD), there was good news this week. Officials say the U.S. Department of Defense has committed to finding alternative methods to safely dispose of obsolete munitions. However, precisely when that policy change is funded and implemented at BGAD remains to be seen.

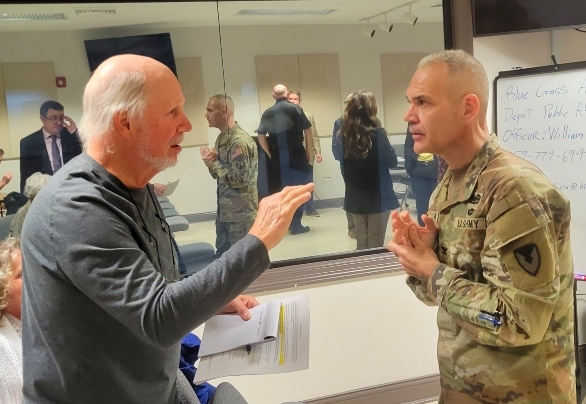

Colonel Brett Ayvazian, commander at BGAD, delivered the news on Wednesday at a public information meeting at the Madison County Joint Information Center.

“Just last week we received word that the Department of Defense made the official decision to go ahead and pursue alternate technologies for demilitarizing conventional munitions,” Ayvazian said. “That technology will eventually be pursued and implemented. That said, that campaign is going to take a lot of time and a lot of resources to figure out the best technology and the best way to demil all of these munitions. Until that is developed, we are going to have to rely on our current methods of demil, which is open burning and open detonation.”

Officials explained that there are 11 sites operated by the U.S. Army Joint Munitions Command around the continental United States that have open burn/open detonation permits. They are charged with destroying obsolete munitions before they can become a hazard to service people or the surrounding facilities. BGAD processes only 1.5 percent of the total munitions to be destroyed. BGAD’s main mission is to process munitions – receiving, storing, then sending them to where they are needed. Additionally, part of BGAD’s mission is to refurbish some obsolete munitions, modifying them so they can be used.

Not destroying munitions would likely cause a processing backup that would interfere with BGAD’s main mission of resupplying the armed forces, and it would create a need to store them, which could potentially create a hazard, Ayvazian said.

“The longer it sits, the more unstable it gets, the more danger it presents to human health and safety,” Ayvazian said. “That is why we do the detonation and demilitarization.”

Two issues were on the minds of citizens who attended the meeting. Some expressed concern about the potential impact of open burning and open detonation on air quality and public health, while others asked about noise and possible structural damage caused by the explosions.

Berea resident Craig Williams, who successfully spearheaded the effort advocating for an alternative to chemical weapons incineration at the depot, asked whether static detonation chamber technology currently available at the depot could be used to destroy conventional munitions without open burning or open detonation.

Ayvazian and other officials explained there are three problems with using the existing static detonation chambers; capability, capacity, and safety to human life and the environment. Because the current systems on base are not designed to handle larger munitions, high explosive or fragmenting ordinance, using the current technology might not be safe for that purpose, since they would have to be cut down to fit into the system. Additionally, because the current static chamber system has a smaller capacity, there would inevitably be a munitions destruction backlog, creating the need to store potentially unstable ordnance, officials said.

“It is capable of being retrofit? Probably yes. But the Army decides where that capability is going to go,” said Ayvazian.

Scientists and technicians connected with JMC operations said that when munitions are burned or detonated, several steps are taken to ensure public safety and environmental protection. When munitions are detonated, they are cushioned between three feet of soil on the bottom and six feet over the top of the payload to limit exposure and muffle noise, said Rod Ody.

Additionally, the air surrounding the detonation is captured and sampled by drone, and results are shared with regulatory agencies, such as the Kentucky Department of Environmental Protection (KDEP) and the Environmental Protection Agnecy. At one point, Williams asked whether potentially harmful substances released into the air were within regulatory standards.

“Most of the data shows that the constituents coming off of these operations are within permitted levels,” replied Dr. Keith Clift, JMC Senior Physical Scientist.

Williams followed up by citing a report from KDEP from April of last year, stating that some of the effluents contain hazardous constituents, and that they “are of significant concern to human health and the environment.”

“I don’t think anybody is denying that there are hazardous constituents in this material, the question is how do you monitor the impact of the total amount of hazardous constituents coming off the OD or OB sites on a regular basis?” Williams said.

Officials said the safety of the process has been monitored for over 30 years, while Clift noted that scientific models are employed as a reference to ensure public safety. Ody added that weather conditions are monitored up-to-the-minute before each detonation and burn, gauging wind, potential storms, visibility, cloud cover and other factors to determine if it is safe to proceed with a detonation or burn. When weather presents a risk, the job is called off, he said.

At one point, Williams assured officials that he was merely searching for answers.

“Let me just say, for the record, that we’re all friends here,” Williams said. “We’re all looking for the same result. Historically, I might have been seen as somewhat of an antagonist towards the operations there, but I just want to reassure you that my interest is getting to the best result for the greatest number of people while also satisfying our military mission at the same time. I’m just trying the figure out the best way of going about this.”

Madison County Judge Executive Reagan Taylor and Berea Mayor Bruce Fraley attended Wednesday’s meeting, along with Madison County Magistrate Tom Botkin. Botkin said he has fielded concerns about the detonations from his constituents.

Ayvazian assured citizens property damage was not occurring as a result of the detonations, noting it would take a 30,000-pound explosive to do actual property damage to surrounding structures, but that only 100 pounds of explosives are detonated at a given time, he said. When Botkin asked whether technicians could lower the size of the payloads, thus limiting the noise and concussions from the explosions, Ayvazian said that could be explored.

“The fact that they are willing to look at lightening those loads, that’s a step in the right direction for me,” Botkin said following the meeting. He noted that while the detonations may not cause actual structural damage, they can still be unsettling to neighboring residents. “When people call you who are on Crooksville Road, telling you their dishes are shaking, they aren’t making it up. That may have been a one-time payload, but I just know I get those calls,” Botkin said.